Artworks that Can Be Continually Reworked are the Most Interesting

An Interview with ASAI Yusuke (Artist)

Interviewer: OZAKI Tetsuya

Asai Yusuke was recently awarded the Special Award by Host during Rokko Meets Art 2012. Asai is a popular artist who creates unique fable-like works, from his pictures of plants done in masking tape and pen termed, “Masking Plant,” to his “doro-e” (mud painting) created by using the soil taken from a visited location. He was given the award for his work, Nekko no Kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable, painted inside the Rokko cable car and station building. An artist who chose not to attend art university and instead followed an independent path, we asked Asai about his view of art and source of creativity.

— Congratulations on winning the Special Award by Host. First, what are your feelings about winning this award?

I haven’t received many awards up to now, and since it is an award for artists chosen from public submissions, I was really surprised. And few painters participate in this kind of art project, so in that way I was happy.

— You were awarded this time for the work exhibited inside the cable car and station building, right?

- Nekko no kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable September 2012, Rokko Sanjo Station

Originally, I made “masking plant” works in the city in a guerrilla-like manner, so I was often kicked out by station workers. This time was also a work inside a train, but I was told instead, “Please do it,” and was watched over during the creative process, so it was a strange feeling.

— Do you feel you are like a graffiti writer?

- Nekko no kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable September 2012, Rokko Sanjo Station

Yes, in a way. I don’t really feel like I’m doing something wrong out of a rebellious spirit, but I thought it would be interesting if the train doors opened and you saw a person making a picture. I would bring large sheets of drawing paper and paint while hanging them by the hand straps, but by the time the train reached the next station news had spread that “there’s this person in such and such car at such and such door number” and there was a time when I was immediately kicked out after the doors opened (laugh). But I don’t just leave the works as they are. I’ve made pictures of birds with masking tape in train stations, but in my case, the point is just to make pictures and when I’ve had enough, I take the tape off in the end.

— Have you ever used spray paint or stencils?

I’d like to try, but since I don’t have much courage, I couldn’t go that far (laughter).

By the way, there is an element in my work that is neither finished or unfinished, and it’s fine if someone wants to add something, like a leaf. Once in Fukuoka, there was a time my work was spray painted by a graffiti writer. I made a masking tape piece in the city, and a leaf was added by spray paint. The writer added it at just the right place, and I thought, “This guy really knows what he’s doing.” The writer was even careful not to paint over my tape, going right to the edge. I was really happy.

There was also a time in Yoyogi Park when my work was painted with spray paint, but that was really bad. The person just wanted to stand out, and I felt nothing positive came from it, from the point of view of my work, the park and the artist. It’s clearly divided into “those who understand” and “those who don’t”.

On Discovering Tape and Mud

— Asai-san, your work has also been referred to as Outsider Art (work done by artists with no formal art education or training). I heard you started making art by doing a mural during your high school cultural festival. Did you not paint at all up to that point?

Although I drew pictures in my textbooks during class, the mural was the first time I made art with an intention to be exhibited. And it was some time after that I found artists I liked. I was born in Tokyo and raised in an environment with no nature, so I had a longing for forests as well as a sense of guilt because I didn’t know about nature. I saw a plant behind a park toilet and at times thought, “If I zoom up on this piece of moss, wouldn’t that look like a forest?”

-

- Nekko no kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable September 2012, Rokko Sanjo Station

— Does this mean you started making pictures from a sense of longing for nature?

You know “making pictures” is simply about having fun in the beginning. As a kid, I drew pictures of Super Mario, a video game character. But it wasn’t fun because I couldn’t draw Mario that well. In spite of this I really wanted to draw, so I started drawing the landscape in the background instead. Even if I drew Kinniku Man, I would draw the ring as well. By doing that I could satisfy my “desire to draw”. Ever since I was a child, my purpose was to “draw” and I was happiest when moving my hands. I’m not sure where this comes from, but it hasn’t changed. So while others were drawing characters, I was caught up in drawing fanciful maps like a video game background.

— How did you become interested in using masking tape?

It was the beginning of 2003, and I was making abstract drawings on paper. At that time I had already started using tape in my work. There was a time when I exhibited at Gallery Mabui run by this Okinawan man, and since it was a rental gallery, I had to man the reception desk myself. I thought if I did something, people would come to the exhibition, but I realized there was no one I could invite – I didn’t go to university and I didn’t have any teachers. So that time at the reception desk was incredibly boring. But I couldn’t draw while at the desk, but I had masking tape that I used for hanging the captions, so I started putting masking tape around my pictures. This was the beginning. I drew all night and within a day I had drawn on telephone poles between my house and the gallery. It was like I drew with tape on my way to the gallery and took them off coming home (laugh).

- Nekko no kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable September 2012, Rokko Sanjo Station

— Amazing (laugh)! But why didn’t you go to art university if you had such a desire to draw?

I really had no connection to art, almost to the point where I had never been to an art museum. My parents didn’t mind what I did, but they weren’t going to put out any money, so I had to earn money to buy my own art materials. Since I was told I had to pay my own way through university, I checked tuition fees for art universities and realized it would cost a million or two million yen. I thought, “I could buy a lot of art supplies with a million yen!” In the beginning, out of ignorance, I tried all kinds of materials, from expensive paints to natural pigments used in Nihon-ga and even paints they sell at 100 yen shops.

— When did you discover doro-e (mud painting)?

When I was about 20 years old, I thought, “What is ultimate painting material?” In the end, I thought it would be good if I could use the dirt, water, stone, fire and light around me to make art with. But I didn’t have much confidence to really use them, so I felt it was too soon. I was still immature, and I thought using these materials was something special, almost sacred.

When I went to Indonesia in 2007, I saw a gigantic ghost-like plant, an amazing life force like I’ve never seen before. It’s a tree called banyan. At that time, I thought, “The timing is now,” and decided once and for all to use dirt in my works. Even though I hadn’t experimented and it was a hit-and-miss, for some reason I had this sense of confidence that I could paint with it.

The interesting thing was when I put up the captions for the exhibition. I was asked, “What do you want to write for the materials column?” and I answered, “Dirt and water.” In Indonesian, dirt is called “tanah” and water is called, “air”. As a matter of fact, an Indonesian whom I got to know said, “It says “Motherland” here, you know.” When you combine these two words, they become “tanah air” which apparently means, “Motherland” (laugh). At that time, I felt the distance between me and the material instantly disappear and thought, “Yes, that was the right timing after all.”

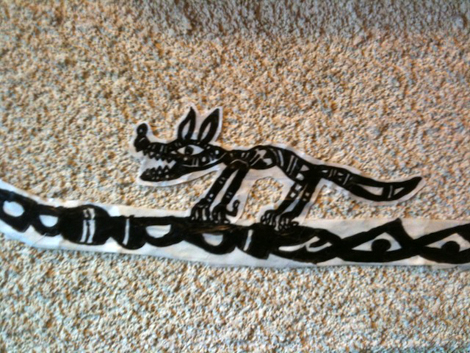

- The biggest mud painting Asai has ever made. April 2012, the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre

Commonalities with Outsider Art

— Asai-san, I feel your style is similar to Outsider Art, and has many similarities especially with Art Brut. You don’t use Western perspective so there is no depth in your work. There is a minuteness and denseness. The same patterns are repeated, and there are many primitive motifs such as animals and plants. And I also feel a certain sense of narrative.

Yes, I think it is similar. I’ve seen a movie called Der Ausflug made by a Japanese director shot at “House of Artists in Gugging” in Austria. It’s a place where many handicapped outsider artists live, and I was shocked to see a man named Oswald Tschirtner and how he was painting in the movie. He uses only lines and his works are incredibly flat. He only makes art as he feels necessary in a very up–front way. It’s nothing special, just one part of his daily life. Drawing is just a matter of fact. On the other hand, it’s different than me. For me, I think it won’t lead to anything if nothing is conveyed. And I’m always thinking of how to improve my works.

But if I make art always in solitude, I become stuck and insecurities come about. In the past, I heard that my friend’s grandfather’s house was empty, so I once hid myself in the mountains of Nagano prefecture. The nights were pitch black, and, since I’m a city boy, I became lonely during (laugh). I drew red monsters like Godzilla and snowmen on Japanese writing paper. I really drew with the spirit of a child, and when I pasted the pictures on the walls, I felt the room was being “protected”. At that time, I thought about outsider artists, and it was like I was saved, like I thought, “Now I understand”.

For me, a world that allows you to make a picture is a good one. But since I really draw a lot, there are many times when I think about “keeping”. The more I paint, the more space my pictures occupy and the rest of world becomes less and smaller. If you see it like that, you can’t be blindly happy drawing. I think artists are kind of bad people.

— On the other hand, don’t you think you are adding something to the world?

You can say I’m adding something, but physically speaking the world becomes smaller, and this means the amount of information is increased. So I have feelings of guilt (laugh). Being an artist is probably about the violent act of “making” and “keeping”.

— There are also similarities to Australian aboriginal pictures, right?

I’m happy to hear that. I’m also pretty interested in Indian Mithila painting and Warli painting. I first saw Warli painting when I was 20 in Yokohama. Using only dots and triangles, they make images of circles, women, and so on. They also make art with rice powder, so I think the influence is definitely there.

— You also use wheat powder, right?

Yes, that’s right. Similar to dirt, wheat flour is found all over the world. For three years, I’ve been going to India annually and I have visited Warli villages. Since everyone is a farmer, “You’re not just making art,” I said. “Why do you ask such a thing,” they answered, looking bewildered. They make pictures to convey their lifestyle. If they don’t farm, they also can’t make art.

- A powder painting

Making Pictures is at the Heart of Me

— It is said you collect the tape off your masking tape works, referring to it as “harvesting”, and create new work with it, calling them “specimen”. Do you mean the things that are yet to be harvested are still living, and the specimens that are created dead?

In a way that’s true. While I think the most interesting condition is “living and remaining”, there are others that are “dead but preserved.” The ones that remain are reworked, and continue in a state of reworking. Similar to architecture such as buildings where people live, it’s interesting if I can leave pictures that are “living yet preserved”. With specimens, it suggests a very finished work, but on the other hand, there are times at an exhibition take down that I couldn’t go to where I would hand a ball or doll-shaped specimen to the staff and they endlessly taping them with the tape that was removed. Then, they are returned in a bigger shape. There are specimens like this case that continue to live, continue to move.

- “specimen (doll)” made from masking tapes

— Is there a possibility that you will move into sculpture or ceramics?

Actually, I’ve always been doing ceramics. In high school, I specialized in ceramics and saw the beauty of natural clay from that time. In February of this year when I exhibited at Azamino, I made a work titled, Ochawan-jima, made up of many tea bowls piled up on each other.

Nevertheless, I’m centered on drawing, and it’s my specialty. I’m making ceramics, sculpture and eat and walk like I’m making one picture. I’ve made a lot of Masking Plants and doro-e paintings, I always have a feeling like I’m creating a work that continues the previous. After the previous work is erased, I make another, or within in a natural flow a picture I’ve made will become a sculpture. I think it would be great to create that kind of positive environment, that kind of natural flow.

- Nekko no kakurenbo @ Rokko Cable September 2012, Rokko Sanjo Station

ASAI Yusuke

Born in Tokyo, 1981. Graduated from Kanagawa Prefectural Kamiyabe High School (Ceramics Course). In 2008, exhibited at KITA!! Japanese Artists Meet Indonesia held in Indonesia, and in 2010 he participated in Aichi Triennale 2010. In 2009, he received the Ohara Museum of Art Award, Exhibition of VOCA 2009. He is also extremely active making outdoor artworks and mural pieces. Rokko Meets Art 2012 will be on until November 25th.

(English translation: Eric Luong)

(Publication: 26 October 2012)