Review / Noh Junction Lady Aoi / Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Stunned and in stitches – the lingering aftereffects of Lady Aoi and The Double Shadow (Watanabe Moriaki / Takatani Shiro)

Ukai Satoshi

What exactly was that I saw? Three weeks on and the stunned, almost shellshocked sensation has yet to subside. It was theater suffused with the continuity of a single, powerful piece of work, revealing in stark fashion the differences in genre between “Noh Junction” and “multimedia performance.” All the while receiving and resisting delicately, and uncompromisingly, yet with unparalleled elegance, the memories, legacies and vestiges of multiple eras, and many brilliant individuals.

Roaming the boundary between this world and the other in Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi) is not only Genji’s official wife, plagued by an ikiryo, vengeful spiritual projection of Lady Rokujō, but a Formula One race-car driver hovering on the brink of death following an accident. A reincarnation of one of the retainers who caused “The Struggle for the Carriage” at the Kamo Festival, said driver (Shigeyama Doji) becomes the focus of dramatic vertigo after a triple-layered switch from supporting role to protagonist, from Heian period to present day, and from female to male. One cannot help but recall with renewed astonishment how Watanabe Moriaki was already exploring such adventures in the 1980s, in collaboration with Kanze Hideo. The critical quality of this latest offering was also clearly demonstrated by the fact that Yuasa Joji’s Musique concrète forms the matrix for this boldest of deconstructions, or perhaps the conditions enabling it. Thus the audience is transported to a kind of no-man’s-land of indeterminate era, ambiguous to the extent that somehow the demon (ie, the ikiryo) (Kanze Tetsunojo), protagonist in the second half, conjures up visions of Goya’s phantoms. Doubtless this staging also self-consciously tried to parade Noh’s capacity as a dramatic form to be such a fearsome stealer of souls.

L’ombre double (The Double Shadow) could be described as an “event” in the strongest sense of the word. Why? Because it represents probably the first explosion of “Claudel laughter,” one of the greatest mysteries of 20th century literature and that most difficult of emotions to contemplate and place, onto the Japanese-language cultural scene.

The very premise of a shadow speaking in the first person is odd to start with. Moreover, this is a shadow without a “master.” Like an abandoned illegitimate child, it heaps blame on the man and woman who ought to be its “masters.” The shadow’s burning grudge, is manifested as just that, like a self-parody come from far, far away. The very idea for this production demonstrates how the concept for a long drama is reflected, in unusual form, in this short dramatic poem resembling a comedic piece, performed around halfway through Claudel’s Le Soulier de Satin (The Satin Slipper).

In his program summary of the thinking behind the production, Watanabe Moriaki states that neither the 1987 staging of The Satin Slipper by Antoine Vitez nor the 2003 production of Olivier Py were especially convincing, particularly when it came to this scene. Thus in the work of composition and directing, Watanabe Moriaki’s highly original view – as a translator and director – of Claudel is expressed in concentrated form. Moreover, by bringing to the stage an almost miraculously accomplished production, via his collaboration with Takatani Shiro, an outstanding artist of a different generation, different cultural context and with different thinking patterns and sensibilities, it would be fair to say Watanabe has made this production a literally exceptional “event.”

Occasionally the shadow of an insect crosses the visual of the white wall, apparently shot on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. After gazing at it for some time, Shirai Tsuyoshi and Terada Misako begin to dance inside a single piece of black fabric, with the wall as backdrop. The comical, writhing motion of their shadows sets the tone for the work.

The Double Shadow rests on a double sacrilege: that of the forbidden love of conquistador Don Rodrigue and the married Dona Prouhèze, uniting not only hearts but bodies to trace a single shadow on this world; and the sacrilege of laughter that from a theological perspective invites rejection as belonging to the domain of the Devil, and emerges from the very foundations of this first sacrilege. Moreover, the humor is divorced from any demonical sneer; on the contrary, it is testament to a great depth of faith. Cocteau had already paid the greatest respect to this truly unique “Claudel laughter” more physiological than psychological, while Genet found therein most of his core motifs from his theater period onward. Without tracing closely the echoes of confrontational dialog with Claudel in their work, we cannot hope to fully understand either Les Paravents (The Screens) or Un Captif amoureux (Prisoner of Love).

Watanabe Moriaki attempts to invite – via at least three routes – the sort of bodies capable of harboring laughter into a cultural space where at first glance they appear to be absent. He does so firstly by positioning the dramatic language firmly in physicality. This means a script that is nothing less than “a poem for the stage that seeks to create a ‘different way of being’ for the body including even the actors’ physiology” (The Satin Slipper, volume 1 commentary), and under the exceptional circumstances of a shadow without a body speaking independently, that physicality is expressed, paradoxically, with even greater purity. This conversion into exquisitely carved and polished Japanese, right down to the rhythm of the words and resonance of the sounds, shows Watanabe Moriaki to be the undisputed master of this field, raising contemporary literary translation to a virtually unsurpassable standard.

Watanabe’s second route is to emphasize the Mallarméist lineage of Claudel’s drama. Here Pierre Boulez’s composition Dialogue de l’ombre double takes the concept of the “eternal book” or “words that will never wither” and interposes it in the imagery of a “cosmic book” corresponding to the whole of a Satin Slipper studded with heavenly myths from east and west, including Japan’s Tanabata legend of the Weaver and Cowherd. The moment at which the figures of the two dancers appear on the opposite side of the Milky Way, amid the particularly beautiful strains of Tono Tamami’s sho woodwind, is unforgettable.

And lastly, Watanabe introduces narrative elements from East Asia. Reading aloud from the Chinese tale Han Ping and His Wife is an attempt to find in the composition of this cultural space, the conceptual vein of The Double Shadow. Thanks to its best guide, the work The Satin Slipper, the main part of which was written in Japan, may be attempting to reincarnate right now within us. How else to explain this blissful state?

Ukai Satoshi

Born 1955, Tokyo. Researcher in French literature and thought. Professor, Hitotsubashi University.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

—

Noh Junction Lady Aoi / Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Watanabe Moriaki / Takatani Shiro

Kyoto Art Theater, Shunjuza / 29, 30 March 2014

Noh Junction Lady Aoi

Performers : Kanze Tetsunojo (30 March), Katayama Kuroemon (29 March), Shigeyama Doji

Music : Yuasa Joji, Lady Aoi, musique concrète, 1961

Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Dancers : Shirai Tsuyoshi, Terada Misako

Narator : Shigeyama Doji

Sho : Tono Tamami

Reading : Goto Kayo, Watanabe Moriaki

Noh Junction Lady Aoi

Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

(at Kyoto Art Theater, Shunjuza / 29, 30 March 2014)

Photos by Shimizu Toshihiro

What exactly was that I saw? Three weeks on and the stunned, almost shellshocked sensation has yet to subside. It was theater suffused with the continuity of a single, powerful piece of work, revealing in stark fashion the differences in genre between “Noh Junction” and “multimedia performance.” All the while receiving and resisting delicately, and uncompromisingly, yet with unparalleled elegance, the memories, legacies and vestiges of multiple eras, and many brilliant individuals.

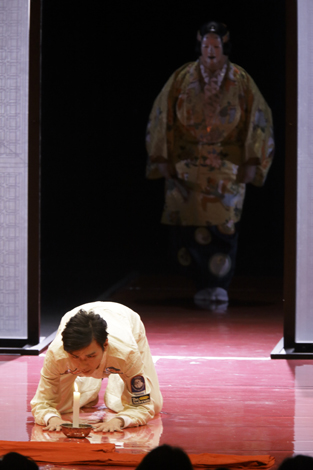

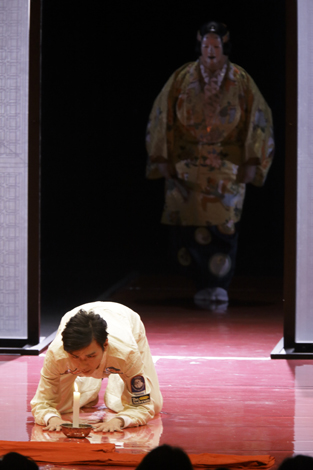

Roaming the boundary between this world and the other in Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi) is not only Genji’s official wife, plagued by an ikiryo, vengeful spiritual projection of Lady Rokujō, but a Formula One race-car driver hovering on the brink of death following an accident. A reincarnation of one of the retainers who caused “The Struggle for the Carriage” at the Kamo Festival, said driver (Shigeyama Doji) becomes the focus of dramatic vertigo after a triple-layered switch from supporting role to protagonist, from Heian period to present day, and from female to male. One cannot help but recall with renewed astonishment how Watanabe Moriaki was already exploring such adventures in the 1980s, in collaboration with Kanze Hideo. The critical quality of this latest offering was also clearly demonstrated by the fact that Yuasa Joji’s Musique concrète forms the matrix for this boldest of deconstructions, or perhaps the conditions enabling it. Thus the audience is transported to a kind of no-man’s-land of indeterminate era, ambiguous to the extent that somehow the demon (ie, the ikiryo) (Kanze Tetsunojo), protagonist in the second half, conjures up visions of Goya’s phantoms. Doubtless this staging also self-consciously tried to parade Noh’s capacity as a dramatic form to be such a fearsome stealer of souls.

Noh Junction Lady Aoi

Shigeyama Doji, Kanze Tetsunojo

Photo by Shimizu Toshihiro

Noh Junction Lady Aoi

Kanze Tetsunojo

Photo by Shimizu Toshihiro

L’ombre double (The Double Shadow) could be described as an “event” in the strongest sense of the word. Why? Because it represents probably the first explosion of “Claudel laughter,” one of the greatest mysteries of 20th century literature and that most difficult of emotions to contemplate and place, onto the Japanese-language cultural scene.

The very premise of a shadow speaking in the first person is odd to start with. Moreover, this is a shadow without a “master.” Like an abandoned illegitimate child, it heaps blame on the man and woman who ought to be its “masters.” The shadow’s burning grudge, is manifested as just that, like a self-parody come from far, far away. The very idea for this production demonstrates how the concept for a long drama is reflected, in unusual form, in this short dramatic poem resembling a comedic piece, performed around halfway through Claudel’s Le Soulier de Satin (The Satin Slipper).

In his program summary of the thinking behind the production, Watanabe Moriaki states that neither the 1987 staging of The Satin Slipper by Antoine Vitez nor the 2003 production of Olivier Py were especially convincing, particularly when it came to this scene. Thus in the work of composition and directing, Watanabe Moriaki’s highly original view – as a translator and director – of Claudel is expressed in concentrated form. Moreover, by bringing to the stage an almost miraculously accomplished production, via his collaboration with Takatani Shiro, an outstanding artist of a different generation, different cultural context and with different thinking patterns and sensibilities, it would be fair to say Watanabe has made this production a literally exceptional “event.”

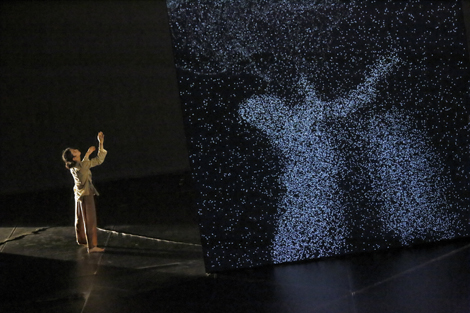

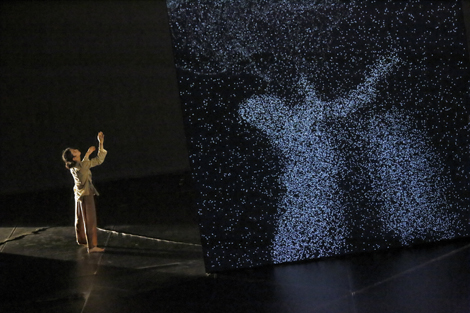

Occasionally the shadow of an insect crosses the visual of the white wall, apparently shot on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. After gazing at it for some time, Shirai Tsuyoshi and Terada Misako begin to dance inside a single piece of black fabric, with the wall as backdrop. The comical, writhing motion of their shadows sets the tone for the work.

Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Sho:Tamami Tohno, Dance: Shirai Tsuyoshi, Terada Misako

Photo by Shimizu Toshihiro

Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Dance: Shirai Tsuyoshi, Terada Misako

Photo by Shimizu Toshihiro

The Double Shadow rests on a double sacrilege: that of the forbidden love of conquistador Don Rodrigue and the married Dona Prouhèze, uniting not only hearts but bodies to trace a single shadow on this world; and the sacrilege of laughter that from a theological perspective invites rejection as belonging to the domain of the Devil, and emerges from the very foundations of this first sacrilege. Moreover, the humor is divorced from any demonical sneer; on the contrary, it is testament to a great depth of faith. Cocteau had already paid the greatest respect to this truly unique “Claudel laughter” more physiological than psychological, while Genet found therein most of his core motifs from his theater period onward. Without tracing closely the echoes of confrontational dialog with Claudel in their work, we cannot hope to fully understand either Les Paravents (The Screens) or Un Captif amoureux (Prisoner of Love).

Watanabe Moriaki attempts to invite – via at least three routes – the sort of bodies capable of harboring laughter into a cultural space where at first glance they appear to be absent. He does so firstly by positioning the dramatic language firmly in physicality. This means a script that is nothing less than “a poem for the stage that seeks to create a ‘different way of being’ for the body including even the actors’ physiology” (The Satin Slipper, volume 1 commentary), and under the exceptional circumstances of a shadow without a body speaking independently, that physicality is expressed, paradoxically, with even greater purity. This conversion into exquisitely carved and polished Japanese, right down to the rhythm of the words and resonance of the sounds, shows Watanabe Moriaki to be the undisputed master of this field, raising contemporary literary translation to a virtually unsurpassable standard.

Watanabe’s second route is to emphasize the Mallarméist lineage of Claudel’s drama. Here Pierre Boulez’s composition Dialogue de l’ombre double takes the concept of the “eternal book” or “words that will never wither” and interposes it in the imagery of a “cosmic book” corresponding to the whole of a Satin Slipper studded with heavenly myths from east and west, including Japan’s Tanabata legend of the Weaver and Cowherd. The moment at which the figures of the two dancers appear on the opposite side of the Milky Way, amid the particularly beautiful strains of Tono Tamami’s sho woodwind, is unforgettable.

And lastly, Watanabe introduces narrative elements from East Asia. Reading aloud from the Chinese tale Han Ping and His Wife is an attempt to find in the composition of this cultural space, the conceptual vein of The Double Shadow. Thanks to its best guide, the work The Satin Slipper, the main part of which was written in Japan, may be attempting to reincarnate right now within us. How else to explain this blissful state?

Ukai Satoshi

Born 1955, Tokyo. Researcher in French literature and thought. Professor, Hitotsubashi University.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

—

Noh Junction Lady Aoi / Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Watanabe Moriaki / Takatani Shiro

Kyoto Art Theater, Shunjuza / 29, 30 March 2014

Noh Junction Lady Aoi

Performers : Kanze Tetsunojo (30 March), Katayama Kuroemon (29 March), Shigeyama Doji

Music : Yuasa Joji, Lady Aoi, musique concrète, 1961

Multimedia performance The Double Shadow

Dancers : Shirai Tsuyoshi, Terada Misako

Narator : Shigeyama Doji

Sho : Tono Tamami

Reading : Goto Kayo, Watanabe Moriaki

(Publication: 7 June 2014)