The world debut of Damien Jalet and Nawa Kohei’s VESSEL

© Damien Jalet|Kohei Nawa, VESSEL 2016 Rohm Theater

All the photos by Yoshikazu Inoue

Reviewed by Ozaki Tetsuya

Out of inky gloom looms a voluminous white installation, resembling a flower fallen to the ground; perhaps a small, flat island; the crater of a volcano; or female genitalia. Symmetrical from the front, its surrounds rise gently in the manner of calyx holding petal; cliffs circling an island; the lip of a crater; labia. The center is slightly indented, and appears to have foam coming out. Is this the eponymous “vessel”? Music plays, quiet, yet disquieting, ominous.

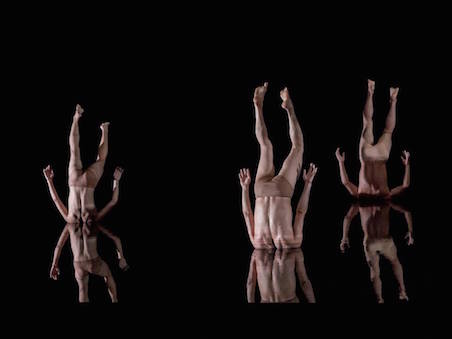

The darkness enveloping the “vessel” shimmers subtly. What seemed simply a dark floor, was in fact water. Three skin-toned masses appear. Swaying gently, they are reflected in the dark of the water’s surface, creating the effect of a giant, vertically symmetrical insect, or mutant creature. Feet appear from the mass at stage left, and it becomes apparent that what we have here are a group of three, and two pairs, of near-naked performers.

A performer separating from the mass at stage left still has water on their back. He/ she faces upward the entire time, but with head covered by crossed arms, hiding the face. Utilizing solely the elasticity of abdominals, spinal column and legs, the dancer moves across the water in the manner of a newly hatched snake, or leech. The others begin to move also, ripples spreading out and casting shadows on the white vessel. Slowly the music grows louder, and a performer at stage left lifts another, depositing them in the water with a crash.

A performer separating from the mass at stage left still has water on their back. He/ she faces upward the entire time, but with head covered by crossed arms, hiding the face. Utilizing solely the elasticity of abdominals, spinal column and legs, the dancer moves across the water in the manner of a newly hatched snake, or leech. The others begin to move also, ripples spreading out and casting shadows on the white vessel. Slowly the music grows louder, and a performer at stage left lifts another, depositing them in the water with a crash. This sound is the signal for a sudden transformation from static to kinetic. The three masses begin to thrash about, splashing water all around. They separate, and the performer who was the first to move stands up, while the other six transition into headstands. Necks and the backs of heads however are in the water, concealing faces from the audience. The standing performer waves his/her arms around dynamically, with head still turned back. The six in headstands spread their legs slightly and sway from side to side as if they were water plants blown by the wind. Amid music recalling the repetitious mechanical noise of a factory, the entire cast plummets to the floor, and the lights go out.

This sound is the signal for a sudden transformation from static to kinetic. The three masses begin to thrash about, splashing water all around. They separate, and the performer who was the first to move stands up, while the other six transition into headstands. Necks and the backs of heads however are in the water, concealing faces from the audience. The standing performer waves his/her arms around dynamically, with head still turned back. The six in headstands spread their legs slightly and sway from side to side as if they were water plants blown by the wind. Amid music recalling the repetitious mechanical noise of a factory, the entire cast plummets to the floor, and the lights go out.  From the next scene, the performers slump forward, folding arms and placing their necks in between, then starting to move. The hollows created by shoulder blades and sinew form shadows that look like eyes. There are fleeting moments when the small of a back resembles eyes, and thus, the whole of the back a long face. At times arms flap rapidly, or grasp ankle bones, but mostly, they form something akin to the lower contours of the face. The moment one detects this, it becomes impossible to think of those moving around the stage as anything but mysterious two-legged creatures with over-sized upper bodies: certainly not human beings.

From the next scene, the performers slump forward, folding arms and placing their necks in between, then starting to move. The hollows created by shoulder blades and sinew form shadows that look like eyes. There are fleeting moments when the small of a back resembles eyes, and thus, the whole of the back a long face. At times arms flap rapidly, or grasp ankle bones, but mostly, they form something akin to the lower contours of the face. The moment one detects this, it becomes impossible to think of those moving around the stage as anything but mysterious two-legged creatures with over-sized upper bodies: certainly not human beings.*

VESSEL is a work of extraordinary ambition. What choreographer Damien Jalet and sculptor Nawa Kohei aimed for with VESSEL was a turning of body into sculpture, that also rendered sculpture corporeal. The result is a revelation: bodies, movements, and a set probably unlike anything ever seen before. A striking visual and aural experience, this is a work destined to never fade from the memory. Yet, it is also more than that.Jalet is fascinated by Celtic culture, by volcano worship in places like Bali and Iceland, and by the ancient Shinto religion and Shugendo (mountain asceticism) of Japan, and has spent many years researching these and other areas of personal interest. In Japan this has included climbing sacred peaks such as Mt. Fuji with dancer Aimilios Arapoglou; walking in the primeval forests of Yakushima, and undergoing training with itinerant monks at Dewa Sanzan. He says the Shugendo belief in ten stages from hell to enlightenment reminds him of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and describes another ritual in which “having observed their own mourning, the devotee is reborn and carried by the mountain as a fetus, gradually passing through the steps to birth over the period of ten days taken to reach the summit” as feeling “very sexual.” (From a conversation with Nawa Kohei, July 1, 2015) Yama, unveiled in the wake of these experiences in 2014, and Ferryman, the film he made with Gilles Delmas, could be described as preparation for VESSEL.

Meanwhile, Nawa notes that during his years as a student at the Kyoto City University of Arts, he repeatedly visited the temples and shrines of Kyoto and Nara to study Buddhist and Shinto figures. His purpose in doing so was to contemplate the kind of works an artist could produce in a world where reverence for the sacred no longer exists. That many of Nawa’s works have a recognizable holiness about them, translated for modern times, is probably due to this experience. His work containing a taxidermied deer for the PIXCELL series of existing objects covered in transparent glass beads had an especially strong whiff of the numinous. In ancient times, deer were seen as sacred beasts, and one may sense in this work – in addition to the artist’s critique of a modern society where close contact with the rawness of life is largely absent – a powerful aura.

Apparently VESSEL initially had themes such as “life” and “cells,” but as Nawa and Jalet joined forces in Kyoto and discussed the work in greater depth, and explored different materials, it came to encompass motifs like death, rebirth, and the sacred. What the audience sees is actually a mysterious white vessel floating on water; choreography that appears to be inspired by the likes of the shishi-odori deer dance of Japan, or the Balinese Barong dance: something like the Creation, arising from a whole consisting of performers, set, music and lighting, or if that is an overstatement perhaps, something we don’t know, something like the generation of life, something simultaneously emanating horror, and gratitude.

The background to VESSEL is likely informed by elements such as creation myths from various lands, starting with Japan’s Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters); by Georges Bataille’s Acéphale, and by achievements in the humanities and natural sciences, from cultural anthropology to biotechnology. In the second half, for instance, the headless performers crouch on the white vessel, then one scrapes a white substance, neither liquid nor solid, from the center, and begins to paint it on the headless upper bodies. This slimy material looks like some kind of milk, or Sujata’s milk-rice, and perhaps was inspired by a Melanesian belief in the omnipotence of semen.

The headless bodies pressed together reduced from seven to five, then five to three, then to just two. The two entwined bodies separated, one standing, lifting its head and showing its face for the first time, through a white film. However this performer with a head (Moriyama Mirai) continued to sway his upper body, before ultimately sinking down into the vessel. Fans of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind will recall the Giant Warrior that fell without a fight; readers of the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) may be reminded of Hiruko, who though the first-born of Izanagi and Izanami, was deformed and therefore cast adrift.

The headless bodies pressed together reduced from seven to five, then five to three, then to just two. The two entwined bodies separated, one standing, lifting its head and showing its face for the first time, through a white film. However this performer with a head (Moriyama Mirai) continued to sway his upper body, before ultimately sinking down into the vessel. Fans of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind will recall the Giant Warrior that fell without a fight; readers of the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) may be reminded of Hiruko, who though the first-born of Izanagi and Izanami, was deformed and therefore cast adrift. This type of work, the motifs being what they are, often ends up being the kind of production with the creator’s own thoughts very much front and center. However here, the music (Hara Marihiko, with special assistance from Sakamoto Ryuichi), which though basically following the dance, occasionally leads/inspires it; and the simple yet carefully-calculated lighting (Yoshimoto Yukiko), highlight the actions of the dancers, who achieve with the greatest of ease the kind of poses and movements that scarcely seem the work of humans, and even induce a kind of fearful dread in the viewer. The humorous movements of the seven headless figures in the first half, and their comical music backing, were another unforgettable element. VESSEL is a masterpiece, the perfect balance of radical, over-the-top themes and minimalistic, understated performance.

This type of work, the motifs being what they are, often ends up being the kind of production with the creator’s own thoughts very much front and center. However here, the music (Hara Marihiko, with special assistance from Sakamoto Ryuichi), which though basically following the dance, occasionally leads/inspires it; and the simple yet carefully-calculated lighting (Yoshimoto Yukiko), highlight the actions of the dancers, who achieve with the greatest of ease the kind of poses and movements that scarcely seem the work of humans, and even induce a kind of fearful dread in the viewer. The humorous movements of the seven headless figures in the first half, and their comical music backing, were another unforgettable element. VESSEL is a masterpiece, the perfect balance of radical, over-the-top themes and minimalistic, understated performance.(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication of the English version: November 18, 2016)

*VESSEL had its world debut at the ROHM Theatre Kyoto on September 3, 2016. It has since been performed on the island of Inujima in Okayama, on October 15, and from January 26-29, 2017 will be staged as part of Yokohama Dance Collection 2017.