That-which-will-always-be / Observations on Miyanaga Aiko: Nakasora – The Reason for Eternity

Ozaki Tetsya

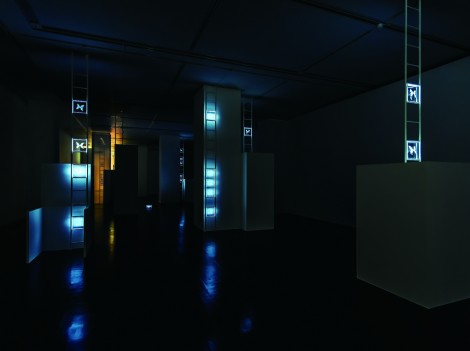

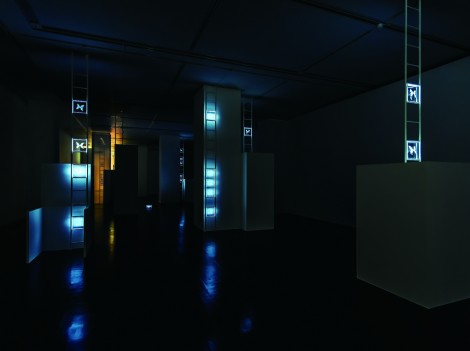

The gallery spaces on the B2 floor of the National Museum of Art, Osaka are notoriously hard to use. The room containing a row of square structural pillars is especially liable to elicit a curse from exhibiting artists. Miyanaga Aiko added several columns, either made from the same material as the structural pillars, or fakes made from white fabric, and erected around them ladders assembled from metal piping, with white butterfly objects in transparent cases inserted between the uprights and crossbars. The white pillars loom faintly out of the gloom, while dozens of butterflies of the purest white sit still, their wings spread. Simply to place ourselves in this tranquil, secluded realm gives us an understanding of the artist’s spatial sense.

In a monochrome world

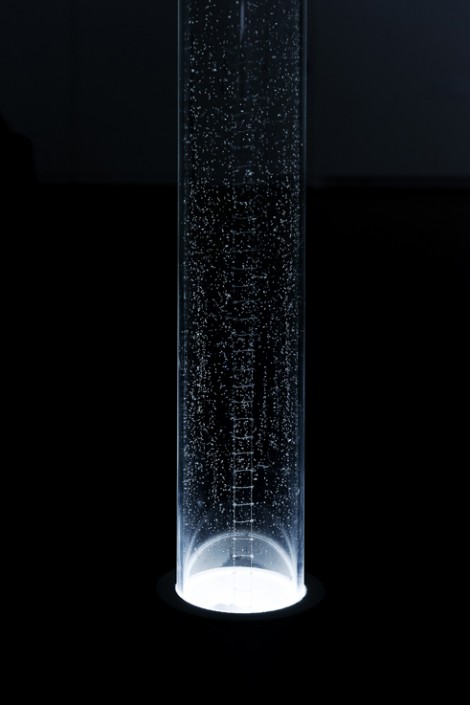

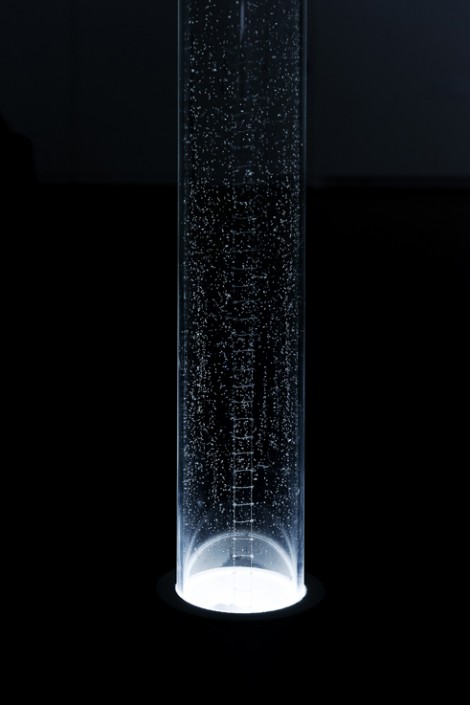

This work shares the same title as the exhibition: Miyanaga Aiko: Nakasora – The Reason for Eternity –. Including it, the show comprises a total of only six works. All are new, with three displayed in front of the room with the pillars. nakasora – puzzle – consists of an array of everyday items from jigsaw-puzzle pieces to an umbrella, arranged in an 18m-long clear plastic case, while nakasora – ladder – features a miniature ladder of delicate thread in a plexiglass case stretching from floor to ceiling. Then there is nakasora – waiting for awakening, an old-fashioned chair with a back, sealed, once again, in clear resin. However, the puzzle pieces, the umbrella, the chair are all fashioned from naphthalene, the butterflies are also made of naphthalene, and the case for ladder also contains naphthalene. As fans of Miyanaga will already be aware, the butterflies, the objects in puzzle and so on will sublime with the passing of time, crumbling and crystallizing on the inside of their cases like pieces of ice. In the same manner, the naphthalene of ladder causes white crystals to adhere to the inside of the case, and the threads forming the ladder.

The remaining two pieces are nakasora – 20 liter ocean – , for which Miyanaga collected brackish water from the Dojima River, not far from the museum, concentrated it, crystallized salt on thread, and displayed it alongside a glass bottle; and nakasora – beginning of the landscape – for which 120,000 orange osmanthus leaves were stripped to their veins and joined like a single piece of fabric. The latter in particular is an epic work involving vast amounts of time and labor. However the finest offering at this show, in my view, would have to be nakasora – waiting for awakening –. As mentioned earlier, white naphthalene in the shape of a chair is sealed in a small clear container. On closer inspection, the resin has vertical geostrata-like stripes, showing how the chair was sealed in stages. At the base of the resin is a small hole, at present covered by a sticker. Once the sticker is removed, the naphthalene, exposed to air, will slowly start to sublime, and after a number of years, decades, maybe even centuries, only the shape of the chair will be left inside the resin.

When a chair is molded from naphthalene, sealed in resin then a hole made to trigger the sublimation process, only the shape of the original chair remains. I don’t know if it is technically possible, but if naphthalene was injected again into the void created in the resin, theoretically a white chair would reappear inside. If this is the case, it makes the naphthalene chair a positive of the original chair, the resin the negative; in other words this work as a whole could perhaps be fulfilling a similar function to that of a photograph. Alternatively, it may act as a kind of fossil, showing the future traces of what once existed. It is certainly intriguing to compare Miyanaga’s works to the likes of photos and fossils.

Photo = Fossil and naphthalene

The artist Sugimoto Hiroshi, who is also known as a collector of fossils, has described photography as “the act of fossilizing the present” (from the catalog for his exhibion L’histoire de l’histoire). Sugimoto has described fossils as a “pre-photographic device for recording time,” but the act of fossilizing the present amounts to none other than the act of moving the present to the past. The instant they are “recorded” in geological strata or on film, the lives of living creatures and photographic subjects are frozen, never to be revived. As Roland Barthes notes in Camera Lucida, the essence of the photograph (and the fossil) is that “this-has-been.” Photographs and fossils certainly record “time,” but this record could just as easily be described as documenting death.

Miyanaga’s white chair may also be a “document of death.” Moreover unlike photos and fossils, which endure for a long time in solid form, her work will eventually sublime, thus causing the original chair to die a second death, perhaps. At some stage the original will lose its form: the wood rotting, its leather tearing, or perhaps simply by being discarded and incinerated. Naphthalene will preserve its external appearance for a time, but ultimately, will itself disappear. Giving it a very fleeting presence compared to the everlasting likes of paper and rock…

The reality though, is different. Miyanaga’s white chair does not show “this-has-been.” Unlike a photo or fossil instantaneously frozen, it is not even stationary. The artist describes it perfectly, saying, “My works are always accompanied by change. Being made from naphthalene – also an insecticide – they start to sublime at room temperature. That is, my sculptural pieces lose their shape over time. …in reality they are not vanishing, but simply recrystallizing in the same space, making the connection to a new form.” (From “On Nakasora”)

So the white chair has only changed its shape, and is by no means vanishing. This makes it not something that “has-been” but something that “is-now,” and “will-always-be.” Similarly, by its very existence it suggests that the original chair “will-always-be.” It also hints that paper and stone too, which are in reality not everlasting and at some stage will lose their original shape, and indeed everything under the sun, by no means vanishes. As the title waking for awakening indicates, the white chair is not dead, nor is it a death mask of the original chair. Rather, right now, strictly speaking, while it remains sealed it is just quietly dormant.

Haacke’s “present” and Miyanaga’s “eternal”

It is also interesting to compare Miyanaga’s work to Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (aka, Weather Cube), the similar form of which comes to mind. Haacke’s cube is an attempt to visualize the circulation of energy in the natural environment by placing a small amount of water in a square clear plexiglass case, and watching the condensation fogging up the inside of the case as it evaporates. Here the “present” is cut out, but this “present” is not a document of death but something better described as a confirmation of life. Water in the case evaporates at room temperature, and having become condensation, once again morphs into liquid. Making it very close indeed to Miyanaga’s work in terms of “not vanishing, but simply recrystallizing in the same space, making the connection to a new form.”

However while Haacke’s interest lies in the “present,” Miyanaga’s seems to lie rather in the “eternal.” It is apparently possible to control to some extent the speed at which naphthalene sublimes. Or take the sound installation soramimimisora, in which the glaze applied to ceramic vessels cracks in the process of expanding and contracting, generating a rare, fragile metallic sound. In an interview with the author Miyanaga said this work (not part of this exhibition) would “produce sound virtually endlessly under the right conditions.” In an essay for the first collection of her works, published for this exhibition, Miyanaga wrote, “The world is constantly changing. […] In the way that clouds appearing in the sky continue to linger there without end, there is no such thing as vanishing.” (NAKASORA: the reason for eternity)

The ladders of various sizes dotted around the venue stretch from floor to ceiling. Looking at them one is reminded of the likes of Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column, or Kusama Yayoi’s Ladder to Heaven. Endless Column is grounded in the folk traditions of Brancusi’s native Romania, and as its title suggests is a pillar-like sculpture, in this case consisting of rhomboid elements joining to stretch seemingly infinitely into the heavens. According to Mircea Eliade in his essay Brancusi and Mythology, the Romanian sculptor was “possessed…by the idea of taking wing into infinite space.” Meanwhile, Kusama’s ladder is made from neon tubes, with mirrors fixed at top and bottom to make it look appear to extend into infinity. It goes without saying that as is clear from prominent Kusama works such as the Infinity Nets series and the exhibition Eternity of Eternal Eternity, she too is an artist obsessed with the endless and eternal.

Perhaps what Miyanaga seeks is indeed “infinite space.” That is perhaps, “eternal time.” Miyanaga’s works lie in eternal time, with the world, and quietly assure us that the world, including her works, will carry on forever, changing its visage along the way.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

Miyanaga Aiko: Nakasora – The Reason for Eternity is showing at the National Musuem of Art, Osaka from October 13 to December 24, 2012. (The pictorial record「Miyanaga Aiko:NAKASORA: the reason for eternity」 , Seigensya)

Ozaki Tetsuya

Born 1955 in Tokyo. Publisher and editor-in-chief of REALKYOTO and REALTOKYO.

The gallery spaces on the B2 floor of the National Museum of Art, Osaka are notoriously hard to use. The room containing a row of square structural pillars is especially liable to elicit a curse from exhibiting artists. Miyanaga Aiko added several columns, either made from the same material as the structural pillars, or fakes made from white fabric, and erected around them ladders assembled from metal piping, with white butterfly objects in transparent cases inserted between the uprights and crossbars. The white pillars loom faintly out of the gloom, while dozens of butterflies of the purest white sit still, their wings spread. Simply to place ourselves in this tranquil, secluded realm gives us an understanding of the artist’s spatial sense.

Photos by Seiji TOYONAGA

In a monochrome world

This work shares the same title as the exhibition: Miyanaga Aiko: Nakasora – The Reason for Eternity –. Including it, the show comprises a total of only six works. All are new, with three displayed in front of the room with the pillars. nakasora – puzzle – consists of an array of everyday items from jigsaw-puzzle pieces to an umbrella, arranged in an 18m-long clear plastic case, while nakasora – ladder – features a miniature ladder of delicate thread in a plexiglass case stretching from floor to ceiling. Then there is nakasora – waiting for awakening, an old-fashioned chair with a back, sealed, once again, in clear resin. However, the puzzle pieces, the umbrella, the chair are all fashioned from naphthalene, the butterflies are also made of naphthalene, and the case for ladder also contains naphthalene. As fans of Miyanaga will already be aware, the butterflies, the objects in puzzle and so on will sublime with the passing of time, crumbling and crystallizing on the inside of their cases like pieces of ice. In the same manner, the naphthalene of ladder causes white crystals to adhere to the inside of the case, and the threads forming the ladder.

The remaining two pieces are nakasora – 20 liter ocean – , for which Miyanaga collected brackish water from the Dojima River, not far from the museum, concentrated it, crystallized salt on thread, and displayed it alongside a glass bottle; and nakasora – beginning of the landscape – for which 120,000 orange osmanthus leaves were stripped to their veins and joined like a single piece of fabric. The latter in particular is an epic work involving vast amounts of time and labor. However the finest offering at this show, in my view, would have to be nakasora – waiting for awakening –. As mentioned earlier, white naphthalene in the shape of a chair is sealed in a small clear container. On closer inspection, the resin has vertical geostrata-like stripes, showing how the chair was sealed in stages. At the base of the resin is a small hole, at present covered by a sticker. Once the sticker is removed, the naphthalene, exposed to air, will slowly start to sublime, and after a number of years, decades, maybe even centuries, only the shape of the chair will be left inside the resin.

When a chair is molded from naphthalene, sealed in resin then a hole made to trigger the sublimation process, only the shape of the original chair remains. I don’t know if it is technically possible, but if naphthalene was injected again into the void created in the resin, theoretically a white chair would reappear inside. If this is the case, it makes the naphthalene chair a positive of the original chair, the resin the negative; in other words this work as a whole could perhaps be fulfilling a similar function to that of a photograph. Alternatively, it may act as a kind of fossil, showing the future traces of what once existed. It is certainly intriguing to compare Miyanaga’s works to the likes of photos and fossils.

Photo = Fossil and naphthalene

The artist Sugimoto Hiroshi, who is also known as a collector of fossils, has described photography as “the act of fossilizing the present” (from the catalog for his exhibion L’histoire de l’histoire). Sugimoto has described fossils as a “pre-photographic device for recording time,” but the act of fossilizing the present amounts to none other than the act of moving the present to the past. The instant they are “recorded” in geological strata or on film, the lives of living creatures and photographic subjects are frozen, never to be revived. As Roland Barthes notes in Camera Lucida, the essence of the photograph (and the fossil) is that “this-has-been.” Photographs and fossils certainly record “time,” but this record could just as easily be described as documenting death.

Miyanaga’s white chair may also be a “document of death.” Moreover unlike photos and fossils, which endure for a long time in solid form, her work will eventually sublime, thus causing the original chair to die a second death, perhaps. At some stage the original will lose its form: the wood rotting, its leather tearing, or perhaps simply by being discarded and incinerated. Naphthalene will preserve its external appearance for a time, but ultimately, will itself disappear. Giving it a very fleeting presence compared to the everlasting likes of paper and rock…

The reality though, is different. Miyanaga’s white chair does not show “this-has-been.” Unlike a photo or fossil instantaneously frozen, it is not even stationary. The artist describes it perfectly, saying, “My works are always accompanied by change. Being made from naphthalene – also an insecticide – they start to sublime at room temperature. That is, my sculptural pieces lose their shape over time. …in reality they are not vanishing, but simply recrystallizing in the same space, making the connection to a new form.” (From “On Nakasora”)

So the white chair has only changed its shape, and is by no means vanishing. This makes it not something that “has-been” but something that “is-now,” and “will-always-be.” Similarly, by its very existence it suggests that the original chair “will-always-be.” It also hints that paper and stone too, which are in reality not everlasting and at some stage will lose their original shape, and indeed everything under the sun, by no means vanishes. As the title waking for awakening indicates, the white chair is not dead, nor is it a death mask of the original chair. Rather, right now, strictly speaking, while it remains sealed it is just quietly dormant.

Haacke’s “present” and Miyanaga’s “eternal”

It is also interesting to compare Miyanaga’s work to Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (aka, Weather Cube), the similar form of which comes to mind. Haacke’s cube is an attempt to visualize the circulation of energy in the natural environment by placing a small amount of water in a square clear plexiglass case, and watching the condensation fogging up the inside of the case as it evaporates. Here the “present” is cut out, but this “present” is not a document of death but something better described as a confirmation of life. Water in the case evaporates at room temperature, and having become condensation, once again morphs into liquid. Making it very close indeed to Miyanaga’s work in terms of “not vanishing, but simply recrystallizing in the same space, making the connection to a new form.”

However while Haacke’s interest lies in the “present,” Miyanaga’s seems to lie rather in the “eternal.” It is apparently possible to control to some extent the speed at which naphthalene sublimes. Or take the sound installation soramimimisora, in which the glaze applied to ceramic vessels cracks in the process of expanding and contracting, generating a rare, fragile metallic sound. In an interview with the author Miyanaga said this work (not part of this exhibition) would “produce sound virtually endlessly under the right conditions.” In an essay for the first collection of her works, published for this exhibition, Miyanaga wrote, “The world is constantly changing. […] In the way that clouds appearing in the sky continue to linger there without end, there is no such thing as vanishing.” (NAKASORA: the reason for eternity)

The ladders of various sizes dotted around the venue stretch from floor to ceiling. Looking at them one is reminded of the likes of Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column, or Kusama Yayoi’s Ladder to Heaven. Endless Column is grounded in the folk traditions of Brancusi’s native Romania, and as its title suggests is a pillar-like sculpture, in this case consisting of rhomboid elements joining to stretch seemingly infinitely into the heavens. According to Mircea Eliade in his essay Brancusi and Mythology, the Romanian sculptor was “possessed…by the idea of taking wing into infinite space.” Meanwhile, Kusama’s ladder is made from neon tubes, with mirrors fixed at top and bottom to make it look appear to extend into infinity. It goes without saying that as is clear from prominent Kusama works such as the Infinity Nets series and the exhibition Eternity of Eternal Eternity, she too is an artist obsessed with the endless and eternal.

Perhaps what Miyanaga seeks is indeed “infinite space.” That is perhaps, “eternal time.” Miyanaga’s works lie in eternal time, with the world, and quietly assure us that the world, including her works, will carry on forever, changing its visage along the way.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

Miyanaga Aiko: Nakasora – The Reason for Eternity is showing at the National Musuem of Art, Osaka from October 13 to December 24, 2012. (The pictorial record「Miyanaga Aiko:NAKASORA: the reason for eternity」 , Seigensya)

Ozaki Tetsuya

Born 1955 in Tokyo. Publisher and editor-in-chief of REALKYOTO and REALTOKYO.

(Publication: 17 December 2012)