Rewiew : KYOTOGRAPHIE 2015: international photography festival

Tristes “tribes” (KYOTOGRAPHIE 2015: international photography festival)

The theme for the third edition of KYOTOGRAPHIE was “TRIBE.” Among the works on display, the most outstanding were the photographs by Martin Gusinde of the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego, Patagonia, and the photographs by Fosco Maraini, who was also an anthropologist, of the ama (female divers) of Hegura-jima Island, Noto. I say this not because they are fresh, (1) nor because, as they say, the essence of photography is recording, and the authenticity of the subject takes precedence over art photography in which creativity is emphasized. But because both transcend the colonial framing (relationship between photographer and subject, gaze) that habitually hangs over anthropological/folkloric photographs as well as photographs that originate in the threshold between two cultures.

Installation view: KYOTOGRAPHIE 2015: international photography festival

Martin Gusinde, The spirit of the Tierra del Fuego people, Selk’nam,Yamana, Kawésqar

(Kyoto City Hall open square, Photo by Takuya Oshima © Takuya Oshima

Installation view: KYOTOGRAPHIE 2015: international photography festival

Fosco Maraini, The Enchantment of the Women of the Sea — by “Museo delle Culture” of Lugano

Traditional building in Gion Shinbashi, Photo by Takuya Oshima © Takuya Oshima

Anthropology developed as a field of study in which Caucasians from the West took as their “research subjects” “uncivilized” tribes from outside the Western sphere, or in other words as a thoroughly colonial field of study. These tribes occupied areas that were colonized by Caucasian settlers or missionaries, and in Patagonia in particular they were driven out or hunted like vermin so that by the mid 20th century at the latest they were extinct. (2) Anthropology represented the flip side of this genocide, and so the reason anthropologists travelled to all parts of the world with cameras and recording equipment at the start of the 20th century to record these dying tribes was none other than because they were conscientious accessories to these crimes.

These documentary photographs employed either a style that treated their subjects as “specimens” (by making them stand facing the camera and capturing them individually or lined up in a row in the center of the frame) or a style that “snapped” them in their “natural state.” The colonial framing was reinforced by these two styles. Their aim was a kind of separatism in which the subject was identified purely as an entity with no association whatsoever with the photographer. The subject (the observed) and the photographer (the observer) and divided and a distance maintained between them.

Well then, neither Gusinde’s photographs of the Indios of Tierra del Fuego nor Maraini’s photographs of the ama of Japan were the first photographs depicting these two subjects. If anything, the two men were both late arrivals, their work based on that of any number of predecessors. (3)

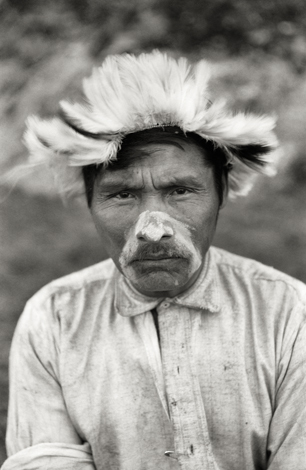

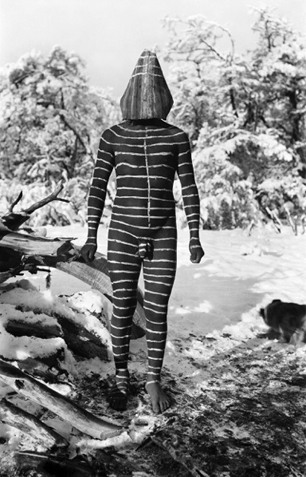

Prior to Gusinde, for example, Charles Furlong photographed the Indios of Tierra del Fuego using the “natural state” snapshot style. (4) Ten years later, many of the Indios in Gusinde’s photographs have Spanish first names and wear Western clothing. It was no longer possible to photograph them in their “natural state.” Gusinde’s photographs are records of rites-of-passage practiced by the Indio’s long ago that were reenacted at his request. This is why instead of presenting these “reenactments” as a “natural state” he chose the specimen style. At the same time, by recording the names of spirits in the case of the rites-of-passage photographs and the names of individuals in the case of the photographs of daily life, he negated their “specimen”-like characteristics. Each “specimen” is transformed into a kind of memorial photograph in which the subjects are named individually. They are “memorial photographs,” or epitaphs, to his “tribe” (there are photographs showing Gusinde himself with the same paint (representing lineage) on his face).

Martin Gusinde, Augusto Balfur, guardian of the Ciexaus hut.Yamana, 1919-1924

© Martin Gusinde / Anthropos Institut / Éditions Xavier Barral

Martin Gusinde, Ulen, the male clown, initiation ceremony of the Hain, a Selk’nam rite, 1918-1924, ca.

© Martin Gusinde / Anthropos Institut / Éditions Xavier Barral

Compared to the memorial photographs of Gusinde, which were shot by way of a dual negation (the negation of nature and the negation of specimens), Maraini’s photographs of ama are full of positive feelings of happiness. Maraini did not have the guilty conscience that dogged the German anthropologist. He originally came to Japan as an anthropologist interested in working in a region where the causes of the destruction of the target ethnic group (in his case, the Ainu people) could not be traced to Caucasian society, which set him apart from his colleagues working in Africa or North or South America. However, it seems that his interest later shifted from recording vanishing ethnic groups to recording folk customs that survived in local communities in the face of the upheavals of war, or in other words from extinction to continuation.

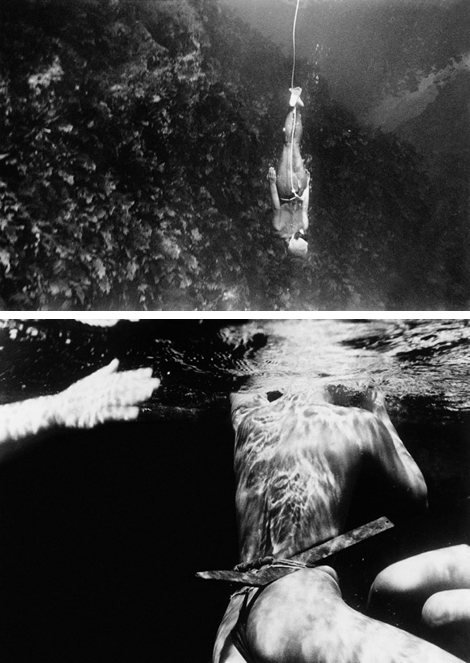

As noted above, “natural state” snapshots are colonial. They unilaterally project onto “innocent” subjects ambiguous meanings, including “records of folk customs,” “eroticism” and “mythical worlds,” adopting a (white male) colonial gaze. Maraini, however, abandoned this ambiguity and plunged into the sea with the ama. It is the underwater photography that resulted from this act that represents the high point of this series. As a result of Maraini immersing his own body in the same medium (seawater) as his subjects, the positional relationship between photographer and subject is rendered unstable and the images fluctuate wildly, as a result of which the colonial framing dissolves completely. Eroticism and mythology come alive the moment when Maraini becomes a participant.

Fosco Maraini, The Enchantment of the Women of the Sea, Japan, 1954

© 2015 MCL – Vieusseux – Alinari

To simply identify with and mutually respect a given “tribe” would amount to no more than friendly separatism. If we were to melt all “tribes” into the great mass of “humanity,” then the “tribe” would disappear. A “tribe” is not a community (“we,” subject) based on identity, but rather it is something that emerges when the subject’s identity wavers as a result of their participation in a community (“people doing x,” verb) through such actions as painting their face or diving in the sea. The photographs of Gusinde and Maraini are “tribe” photographs not because they record the identities of certain tribes, but because they record the wavering of their identity.

2 There is a plausible theory that they were annihilated because they lacked immunity to the infectious diseases introduced by Caucasians, but it goes without saying that settlers from Argentina and Chile who embarked on goldmining and the development of sheep ranches in Patagonia actively eliminated the Selk’nam people, who were nomadic hunters. One well-known settler, a man by the name of Julius Popper, openly admitted to being an “Ona (another term for Selk’nam) hunter.”

See text by Marisol Palma Behnke in Begegnungen auf Feuerland. Selk’nam, Yámana, Kawesqar: Fotografien von Martin Gusinde 1918-1924 (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2015) p. 26.

Left: Popper during a “hunt.” In the foreground is the body of an Indio. Despite this past, with the body painting of the Selk’nam people now famous, likenesses of them are being used to promote tourism. Intolerable shamelessness.

Left: Popper during a “hunt.” In the foreground is the body of an Indio. Despite this past, with the body painting of the Selk’nam people now famous, likenesses of them are being used to promote tourism. Intolerable shamelessness.Right: “Bienvenidos a Tolhuin” – A Selk’nam figure erected at the entrance to an isolated village in Tierra del Fuego (from Google Maps).

3 For Gusinde, the likes of Edward Curtis and Charles W. Furlong, and for Maraini, the likes of Iwase Yoshiyuki and, in the sense that they superimposed the world of Greek mythology over “simple” inhabitants of “nature” by the sea, Wilhelm von Gloeden’s photographs of young fishermen in Taormina, Sicily.

4

Charles Wellington Furlong, “The Vanishing People of Land of Fire”, in: Harper’s Magazine, January 1910. http://harpers.org/archive/1910/01/the-vanishing-people-of-the-land-of-fire/

Charles Wellington Furlong, “The Vanishing People of Land of Fire”, in: Harper’s Magazine, January 1910. http://harpers.org/archive/1910/01/the-vanishing-people-of-the-land-of-fire/Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Author of Hibi kore shashin (Everyday this photography) and Pururamon – tansu ni shite fukusu no sonzai (Pluramonity – on the existence of plurality in the mono), among others. Has also contributed texts to English-language exhibition catalogues and monographs for artists including Daido Moriyama, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Wolfgang Tillmans.

(Publication of the English version: June 5, 2015)

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)—

KYOTOGRAPHIE 2015: international photography festival / 3rd EDITION April 18th – May 10th, 2015