Mise Natsunosuke: Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–

Mise Natsunosuke and Tohoku-ga – Can a new order arise from chaos?

Hattori Hiroyuki

Mise Natsunosuke was born in Nara and studied Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) in Kyoto before returning to Nara to teach art at high school. He later studied abroad in Florence, and after returning to Japan he moved to Yamagata, where he is currently based. As an artist he is endowed with considerable breadth and complexity, being at once inspired by the various locations he personally experiences based on his strong interest in folklore and possessed of an attitude of perfect composure in consistently confronting “Japan” and its history.

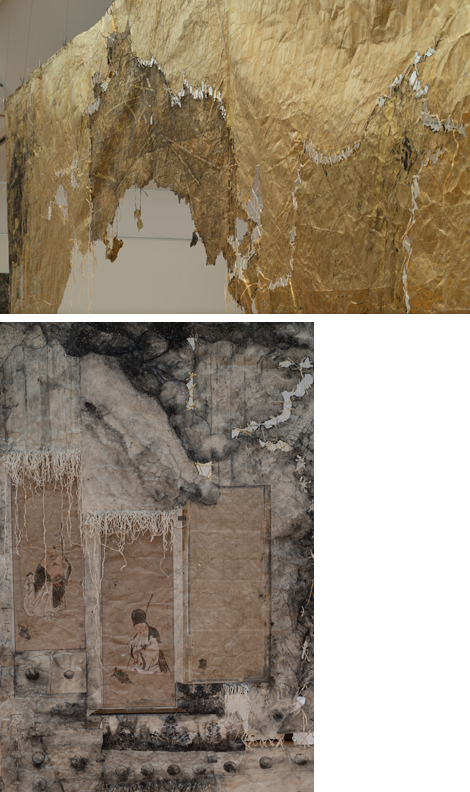

At this exhibition, a new work entitled Painting of Japan –basso ostinato– was unveiled. The term “basso ostinato,” which is also used in the exhibition title, is a musical term referring to a version of the technique of ostinato in which the same musical voice persistently repeats in the bass register. The Japanese philosopher Maruyama Masao used this same term to explain the peculiarly Japanese metamorphosis that occurs when foreign ideas are introduced into this country. (1) Such is the background to this work, which is one of a series of massive, banner-shaped pieces Mise has taken on in recent years that have as their motif the “Japan Sea Countries Map” (commonly known as “The Upside Down Map”), which Mise has referred to on several occasions in the past. (2) The work is hung from the ceiling, in which numerous eyelet holes have been made, in a manner that is rough to an extent unimaginable for normal Nihon-ga. The paper has been extended in an equally rough manner and embedded with various elements using collage, and in many places the different pieces of paper are fastened together with string.

If one steps back slightly and traces the outline held together by the string, a certain form emerges. It is a map of Japan turned upside down. Most of us probably think of Japan as located to the right (the easternmost extremity) of Asia with the Pacific Ocean lying even further to the right (the east), but this map urges us to reconsider this understanding of the world. Although not depicted in this work, the original “upside down map” shows Russia and mainland China below the Japanese archipelago, which looks not unlike a lid on top of the Asian continent. According to Mise, another, separate work exists that depicts the mainland including Russia, China and the Korean peninsula on the bottom half beyond the Sea of Japan. (3) Moreover, if this work depicting the bottom half and the work in this exhibition are joined together, the torn out Sea of Japan areas match up and a circular hole reminiscent of the Rising Sun flag appears. One could also say that the appearance of the Rising Sun flag as a massive hole that forms in our imagination represents the structure of the hollow world of Japan that consists solely of multiple fringes around an empty center. Viewing it up close, one can appreciate that Mise’s work comprises various images weaving together the abstract and the concrete depicted relentlessly and in detail, but if one pulls back slightly and views the entire composition, it becomes clear that the congregation of voids formed by the shapes of the individual pieces of attached paper and the way they are combined depict an ominous Rising Sun-like symbol as a symbol of absence. The mystery of Mise’s artwork probably stems from the manner in which this almost myopic, personal inner expression and birds-eye view-like sense of distance that seeks to depict the overall structure of the world form a harmonious whole.

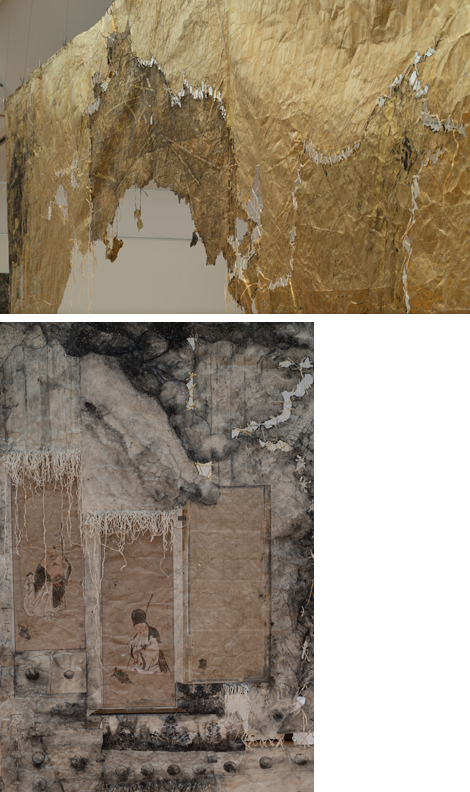

Incidentally, there are several parts of this new work that look familiar. Mise is in the habit of dismantling previously unveiled works and absorbing the parts into new works. The set of three hanging scrolls embedded in this work as well as the parts collaged with newspaper were previously part of the work unveiled in 2013 under the title My God. By using repeatedly according to a set rhythm the same materials, forms and symbols, by building them up into layers and varying them slightly each time, he produces pictorial map-like works of art. Variations of these same elements are used again in different works addressing different themes. As if rejecting completion or fixation, he seeks by transcending time and place and through persistent repetition and minute variations to continually change.

This sense of a harmonious whole in which various elements are embraced in their original chaotic state with no effort made to resolve them calls to mind “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”, which Mise was involved in at the same time as this exhibition. (4) This project provides a space within a university setting for an alternative art education (or learning) where university students can question for themselves such things as “art,” “community” and “society” and each explore universal forms of expression based on their own individual locale. It originally began as a part of the educative process with Mise himself taking the lead in tutorials and creative activities, but it now seems that for Mise it has become an indispensable creative environment that complements his educative activities. And while there is undoubtedly some turnover in the student membership and changes to the scale and atmosphere each year, such changes are regarded positively, and the collaborative manner in which various contradictions and conflicts are embraced while maintaining the harmonious whole also speaks to a lack of a desire for resolution.

With respect to “Tohoku-ga,” the students have a strong interest in folkloric works, and based on meticulous research they seek to produce work that satisfies their desire for a harmony between the particularity that is reliant on personal stories arising from the locale of Yamagata in the Tohoku region, universality and the broader concept of history. It would appear that this methodology is in fact identical to Mise’s own. Perhaps by sharing widely the methodology he himself has singled out and putting it into practice as a group, he is seeking to spark some kind of broader movement beyond the simple artists collective. If we regard his sharing of his knowledge and experience and his establishment of a collaborative platform in the form of “Tohoku-ga” as an attempt to generate a groundswell of fresh creative expression, then his simultaneous presentation of his own solo show and works associated with “Tohoku-ga” makes greater sense. The kind of direction this initiative will take in the future is anybody’s guess, but at the least it has continued steadily for close to six years, including even shows at public art museums, and by continuing to steadily produce work while at the same time taking on new challenges, such as realizing collaborations with leading artists such as Yanagi Miwa as seen in the work presented at this latest exhibition, and by slowly but steadily reverberating and resonating as if persistently producing a bass note at a steady rhythm, while it is unlikely that it will become a radical revolution, the day may come when it will open up a new field of expression in the form of a new kind of collaboration that slowly foments. Could the new groundswell that is the nebulous “Tohoku-ga” group swirling around Mise at its center give rise to a new movement of artistic expression with a definite order?

—

Hiroyuki Hattori

Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1978, Hattori completed postgraduate studies in architecture at Waseda University in 2006 before becoming curator at Aomori Contemporary Art Centre [ACAC], Aomori Public University in 2009. He is also working as one of the curator for Aichi Triennale 2016. His constant pursuit of “alternative” setups has led to the establishment of art spaces—all known by the abbreviation “MAC”—in Japan and overseas. Recent curatorial work includes Towada Oirase Art Festival “Survive: Time Hoppers on the Earth” (Towada Art Center and other sites in the Oirase area, 2013) and the collaborative project co-curated by 13 curators from 7 countries “Media/Art Kitchen” (Galeri Nasional Indonesia, MAP KL, Ayala museum, BACC, YCAM, ACAC | the Japan Foundation, 2013–14), among others.

—

1. From the text by Mise Natsunosuke included in the exhibition flyer.

2. A map prepared by Toyama prefecture in 1994 and republished as a revised edition in 2008. It is available for purchase from the Toyama Prefecture Publications Center. It is referred to in Amino Yoshihiko, “Nihon” to wa nanika (History of Japan, Vol. 0: What is “Japan”?), (Kodansha, 2000), among other publications.

3. Exhibited as part of the “In Our Time: Art in Post-industrial Japan” exhibition held at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa from April 25 to August 30, 2015.

4. An autonomous zone of activity formed in 2009 centered on Mise, who teaches Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) at Tohoku University of Art and Design, and Kozaki Masatake, who teaches Western-style painting at the same institution, as a tutorial activity considering “art” in the “Tohoku” region. At this exhibition, original drawings of decorations for the mobile stage truck produced in 2014 in collaboration with Yanagi Miwa were displayed as “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

“Mise Natsunosuke: Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–” and “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”

“Mise Natsunosuke: Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–” and “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”

7 April 2015 – 26 April 2015, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art

Mise Natsunosuke was born in Nara and studied Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) in Kyoto before returning to Nara to teach art at high school. He later studied abroad in Florence, and after returning to Japan he moved to Yamagata, where he is currently based. As an artist he is endowed with considerable breadth and complexity, being at once inspired by the various locations he personally experiences based on his strong interest in folklore and possessed of an attitude of perfect composure in consistently confronting “Japan” and its history.

At this exhibition, a new work entitled Painting of Japan –basso ostinato– was unveiled. The term “basso ostinato,” which is also used in the exhibition title, is a musical term referring to a version of the technique of ostinato in which the same musical voice persistently repeats in the bass register. The Japanese philosopher Maruyama Masao used this same term to explain the peculiarly Japanese metamorphosis that occurs when foreign ideas are introduced into this country. (1) Such is the background to this work, which is one of a series of massive, banner-shaped pieces Mise has taken on in recent years that have as their motif the “Japan Sea Countries Map” (commonly known as “The Upside Down Map”), which Mise has referred to on several occasions in the past. (2) The work is hung from the ceiling, in which numerous eyelet holes have been made, in a manner that is rough to an extent unimaginable for normal Nihon-ga. The paper has been extended in an equally rough manner and embedded with various elements using collage, and in many places the different pieces of paper are fastened together with string.

Mise Natsunosuke,Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–, 2015

Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Photo by Omote Nobutada

If one steps back slightly and traces the outline held together by the string, a certain form emerges. It is a map of Japan turned upside down. Most of us probably think of Japan as located to the right (the easternmost extremity) of Asia with the Pacific Ocean lying even further to the right (the east), but this map urges us to reconsider this understanding of the world. Although not depicted in this work, the original “upside down map” shows Russia and mainland China below the Japanese archipelago, which looks not unlike a lid on top of the Asian continent. According to Mise, another, separate work exists that depicts the mainland including Russia, China and the Korean peninsula on the bottom half beyond the Sea of Japan. (3) Moreover, if this work depicting the bottom half and the work in this exhibition are joined together, the torn out Sea of Japan areas match up and a circular hole reminiscent of the Rising Sun flag appears. One could also say that the appearance of the Rising Sun flag as a massive hole that forms in our imagination represents the structure of the hollow world of Japan that consists solely of multiple fringes around an empty center. Viewing it up close, one can appreciate that Mise’s work comprises various images weaving together the abstract and the concrete depicted relentlessly and in detail, but if one pulls back slightly and views the entire composition, it becomes clear that the congregation of voids formed by the shapes of the individual pieces of attached paper and the way they are combined depict an ominous Rising Sun-like symbol as a symbol of absence. The mystery of Mise’s artwork probably stems from the manner in which this almost myopic, personal inner expression and birds-eye view-like sense of distance that seeks to depict the overall structure of the world form a harmonious whole.

Mise Natsunosuke,Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–, 2015, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Photo by Omote Nobutada

Incidentally, there are several parts of this new work that look familiar. Mise is in the habit of dismantling previously unveiled works and absorbing the parts into new works. The set of three hanging scrolls embedded in this work as well as the parts collaged with newspaper were previously part of the work unveiled in 2013 under the title My God. By using repeatedly according to a set rhythm the same materials, forms and symbols, by building them up into layers and varying them slightly each time, he produces pictorial map-like works of art. Variations of these same elements are used again in different works addressing different themes. As if rejecting completion or fixation, he seeks by transcending time and place and through persistent repetition and minute variations to continually change.

Mise Natsunosuke,Painting of Japan –basso ostinato–, 2015

Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Photo by Omote Nobutada

This sense of a harmonious whole in which various elements are embraced in their original chaotic state with no effort made to resolve them calls to mind “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”, which Mise was involved in at the same time as this exhibition. (4) This project provides a space within a university setting for an alternative art education (or learning) where university students can question for themselves such things as “art,” “community” and “society” and each explore universal forms of expression based on their own individual locale. It originally began as a part of the educative process with Mise himself taking the lead in tutorials and creative activities, but it now seems that for Mise it has become an indispensable creative environment that complements his educative activities. And while there is undoubtedly some turnover in the student membership and changes to the scale and atmosphere each year, such changes are regarded positively, and the collaborative manner in which various contradictions and conflicts are embraced while maintaining the harmonious whole also speaks to a lack of a desire for resolution.

“Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Photo by Omote Nobutada

With respect to “Tohoku-ga,” the students have a strong interest in folkloric works, and based on meticulous research they seek to produce work that satisfies their desire for a harmony between the particularity that is reliant on personal stories arising from the locale of Yamagata in the Tohoku region, universality and the broader concept of history. It would appear that this methodology is in fact identical to Mise’s own. Perhaps by sharing widely the methodology he himself has singled out and putting it into practice as a group, he is seeking to spark some kind of broader movement beyond the simple artists collective. If we regard his sharing of his knowledge and experience and his establishment of a collaborative platform in the form of “Tohoku-ga” as an attempt to generate a groundswell of fresh creative expression, then his simultaneous presentation of his own solo show and works associated with “Tohoku-ga” makes greater sense. The kind of direction this initiative will take in the future is anybody’s guess, but at the least it has continued steadily for close to six years, including even shows at public art museums, and by continuing to steadily produce work while at the same time taking on new challenges, such as realizing collaborations with leading artists such as Yanagi Miwa as seen in the work presented at this latest exhibition, and by slowly but steadily reverberating and resonating as if persistently producing a bass note at a steady rhythm, while it is unlikely that it will become a radical revolution, the day may come when it will open up a new field of expression in the form of a new kind of collaboration that slowly foments. Could the new groundswell that is the nebulous “Tohoku-ga” group swirling around Mise at its center give rise to a new movement of artistic expression with a definite order?

—

Hiroyuki Hattori

Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1978, Hattori completed postgraduate studies in architecture at Waseda University in 2006 before becoming curator at Aomori Contemporary Art Centre [ACAC], Aomori Public University in 2009. He is also working as one of the curator for Aichi Triennale 2016. His constant pursuit of “alternative” setups has led to the establishment of art spaces—all known by the abbreviation “MAC”—in Japan and overseas. Recent curatorial work includes Towada Oirase Art Festival “Survive: Time Hoppers on the Earth” (Towada Art Center and other sites in the Oirase area, 2013) and the collaborative project co-curated by 13 curators from 7 countries “Media/Art Kitchen” (Galeri Nasional Indonesia, MAP KL, Ayala museum, BACC, YCAM, ACAC | the Japan Foundation, 2013–14), among others.

—

1. From the text by Mise Natsunosuke included in the exhibition flyer.

2. A map prepared by Toyama prefecture in 1994 and republished as a revised edition in 2008. It is available for purchase from the Toyama Prefecture Publications Center. It is referred to in Amino Yoshihiko, “Nihon” to wa nanika (History of Japan, Vol. 0: What is “Japan”?), (Kodansha, 2000), among other publications.

3. Exhibited as part of the “In Our Time: Art in Post-industrial Japan” exhibition held at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa from April 25 to August 30, 2015.

4. An autonomous zone of activity formed in 2009 centered on Mise, who teaches Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) at Tohoku University of Art and Design, and Kozaki Masatake, who teaches Western-style painting at the same institution, as a tutorial activity considering “art” in the “Tohoku” region. At this exhibition, original drawings of decorations for the mobile stage truck produced in 2014 in collaboration with Yanagi Miwa were displayed as “Is Tohoku-ga Possible?”

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 20 June 2015)

7 April 2015 – 26 April 2015, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art