Rewiew : PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015

For the First Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

There’s just one thing dubious about this show.

I suppose the same could be said of any large art exhibition. Doubtless those involved in running it share the same concern. I imagine too, that every visitor is aware of it before they arrive. If everyone knows it, logically there is no compelling reason to write about it here, but touch an open wound, and it smarts. Actively prodding at people’s sore points is the task of the writer, and simultaneously, the task of the reader. What then is the niggling sore point, that single dubious aspect of the curiously named “Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015” exhibition that has appeared in central Kyoto?

Something so ridiculously simple as to be almost anticlimactic, so obvious you may fall off your seat in surprise: the fact that it is impossible to take in the entire exhibition in one day. Now I realize that if you bring together a large body of work by video artists from around the world, it’s unlikely people will watch it all in one day. I entered Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art at 9:30am, and left at closing time, 5pm, having failed to view all the works in there, in their entirety. A tally of the video pieces on show would look as follows: William Kentridge 7 minutes 1 second; Ann Lislegaard 10 minutes 34 seconds, 6 minutes 5 seconds, 5 minutes 42 seconds; Stan Douglas 6 hours 1 minute; Hedwig Houben 20 minutes, 20 minutes; Arin Rungjang 32 minutes 27 seconds, 37 minutes 52 seconds; Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster 3 minutes 58 seconds (5 minutes according to the guide book); Joost Conijn 31 minutes 10 seconds, 28 minutes 37 seconds, 41 minutes 42 seconds, 2 minutes 3 seconds, 20 minutes 24 seconds; Hong-Kai Wang 39 minutes 17 seconds plus multiple reference video/audio tapes; Ahmed Mater 20 minutes; Ragnar Kjartansson 6 hours 9 minutes 35 seconds; Harun Farocki 43 minutes. That’s a total of over 18 hours. Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art is open from 9am to 5pm, giving visitors eight hours to view its contents, and making it impossible from the outset for them to view even half the video material on offer. Perhaps visitors may not be expecting to see all the videos in an international exhibition of this sort in the first place. Yet, for example, if a cinema charged full admission then only screened half the movie, that would be fraud. So surely Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, one of the “main venues” for this exhibition, where it is obvious from the outset that one cannot view all the videos, must be committing fraud?

The above tally purely of screening times only includes straight video works. The Museum is also presenting a cluster of works configured as video installations. If these are added, video screening time at Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art amounts to even more than the aforementioned 18 hours. Obviously, there are non-video works as well, so one’s attention cannot be directed solely at videos. At some point in each work, the visitor has to move on. Which means rising from one’s seat thinking rather despondently, oh well, I suppose this will have to do of this one. Or skipping some altogether. Visitors will probably convince themselves that “that one didn’t look so interesting anyway.” Isn’t this showing art in a way that virtually guarantees visitors will dismiss some as not worth the trouble? Or does the entire responsibility for what is seen rest with the viewer?

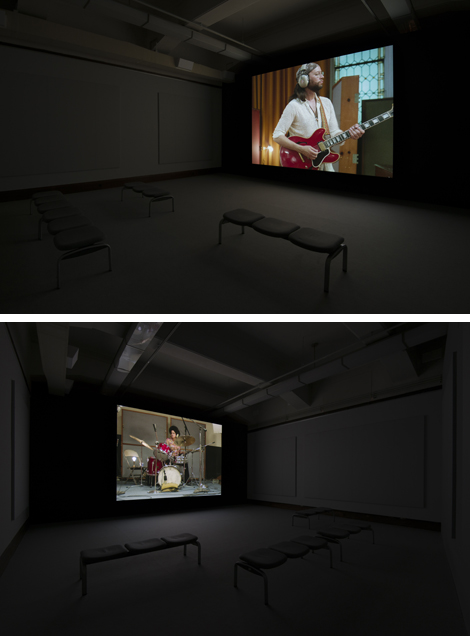

A couple of skilled video-makers have tacitly offered up solutions to this problem: Stan Douglas, with Luanda-Kinshasa (2013) on the ground floor of the Museum, and Tanaka Koki on the second floor near the exit with Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 “1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 Between Man and Matter” (2015). Both display concern for visitors troubled by being forced to give up viewing their works partway through – to such an extent that you wonder if the pair colluded in advance. Stan Douglas screens a performance recreating Miles Davis’ On the Corner, with a completely over-the-top running time of six hours one minute. The album is only originally about an hour long. Stretching it to six hours is thus only playing with different combinations for each track (although not having watched it for the full six hours I cannot say this with absolute certainty). After watching for an hour or so, members of the audience will notice the same footage being mixed in. And that “same footage” will give them the opportunity to move on (although the seductive quality of the video/music is such that you may find it hard to leave. The facial expressions of the attractive female drummer are especially compelling.)

Stan Douglas Luanda-Kinshasa, 2013

Installation views at “Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015”

(Images courtesy Parasophia Organizing Committee)

Tanaka Koki meanwhile has put the videos for his installation here online as they become available. Implying that he is happy for us to take a closer look at the details later. Do not, he is saying, expend all your enthusiasm solely on watching the videos at the show. If you are in a hurry – being near the exit and having run out of time – even a quick glance at the video will suffice, so take in the space as a whole, and concentrate on the display. It might seem a bit lacking, but that’s an illusion. Even the single word “occupation” should evoke such a surfeit of contemporary meanings that you’ll think whooaahh, give me a break… After all, “occupation” has never been more of a talking point than over the past few years. This show is crammed with information waiting to be deciphered, shot through with invisible words. Tanaka Koki’s work champions the principle of proactively reading for meaning.

Tanaka Koki Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 “1946–52 Occupation Era,

and 1970 Between Man and Matter”, 2014-15.

Installation views at “Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015”

(Images courtesy Parasophia Organizing Committee)

If the organizers had the time to proudly declare, “Amid a growing global trend toward ever-larger international exhibitions, this will be an exhibition of just the right size for a city like Kyoto, that is not too large, having over 10,000sqm in display space yet with an emphasis on providing sufficient space and personalized support to a contingent of participating artists deliberately limited in number to 36 artists and artist units (note: this is from the fourth press conference, on January 30, 2015. The final number was 40)” (Parasophia artistic director Kohmoto Shinji), perhaps they ought to have worked harder to come up with better ideas for exhibiting the videos, and for the sake of the audience, demonstrated a greater penchant for editing, that is, asked the artists to make their works a bit shorter. If they were incapable of that, well, they were only following the example of previous international shows in Japan. Come on guys, you can do it…

The best part about Parasophia is not the “main venues” of the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art and Museum of Kyoto, but the freely accessible, free-of-charge exhibition spaces dotted around the city. These are all splendid spaces that definitely deserve further development in any future exhibitions. Especially unmissable are Aernout Mik’s video installation Speaking in Tongues (2013) at the Kyoto Art Center, and Susan Philipsz’ sound art The Three Songs (2015) on the Kamo River delta. The Aernout Mik work in the second-floor lecture hall of the Kyoto Art Center pretty much resembles a silent comedy film. It is indeed, silent. And this very contemporary comedy, staged in a venue such as a lecture hall, is also a device to bring a stream of words springing to the viewer’s mind. The lack of sound reveals an unlikely sort of humor.

Aernout Mik Speaking in Tongues , 2013.

Installation views at “Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015”

(Images courtesy Parasophia Organizing Committee)

Heading to the Kamo River delta, site of Susan Philipsz’ work, I found a scene no different from an ordinary weekend. There were children, and adults. The weather was fine, people were paddling barefoot in the river, or moving to and fro across the stepping stones. Imagining that surely here was a place already complete, with no room for “art” to interpose, I then heard a mysterious voice, singing out of nowhere.

Susan Philipsz The Three Songs , 2015

Installation views at “Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015”

(Photo: Fukunaga Shin)

No one was listening. Yet it was probably audible to all. The singing was not forcing its way onto the scene as “art” but mingling, like a friend. The voice seemed to be soaking its feet in the river, picking its way carefully across the stones. Rolling up its trousers, taking off its shoes and following children as they jumped from one stepping stone to the next to the other side. Saying, hello there. And it seemed to have made friends with the children. Perhaps it was all a trick of the mind. Then I noticed the singing had already stopped, so perhaps it was indeed just my impression, a delusion, but I could believe this work by Susan Philipsz had been created to permit such delusions. In my view, the singing had turned up to greet us, to meet and spend time with children and adults in that place. There can be no room for allegations of fraud here, because friendship is not about what you can get out of being friends.

March 27, 2015

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)(Publication of the English version: April 20, 2015)

—PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015 | REALKYOTO | (Index of related articles)

Review : Asada Akira: PARA-PARASOPHIA: On the sidelines at the Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Fukunaga Shin: For the First Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Takahashi Satoru: PARASOPHIA – Institutional Engagement

—

Official Site : PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015